SOLID: The First 5 Principles of Object Oriented Design

SOLID is an acronym for the first five object-oriented design (OOD) principles by Robert C. Martin (also known as Uncle Bob).

It stands for:

S - Single-responsibility Principle

O - Open-closed Principle

L - Liskov Substitution Principle

I - Interface Segregation Principle

D - Dependency Inversion Principle

Single-Responsibility Principle

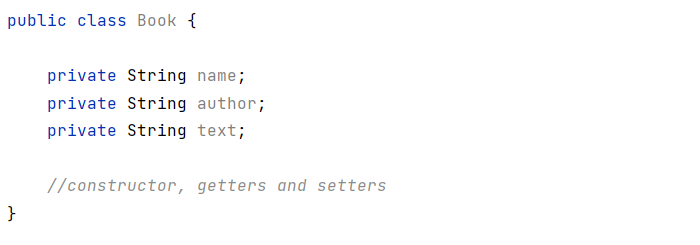

The Single-Responsibility Principle (SRP) states that a class should have one and only one reason to change, meaning that a class should have only one job. Let’s look at a classic example of a simple book class:

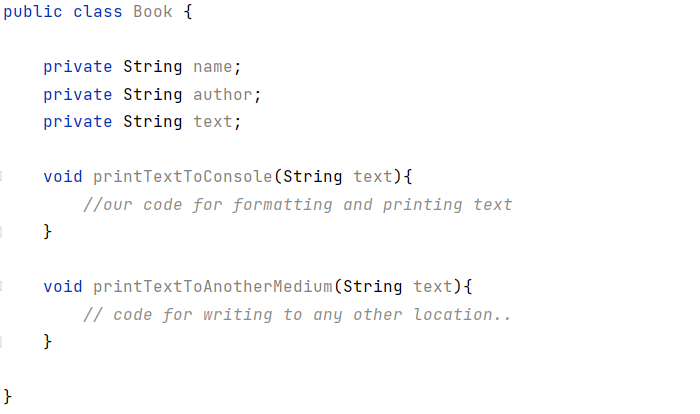

We have a class that stores data about books. However, we can only store information, and we can’t do much more. Let’s add a print method. Now it is possible to print, but this code violates the single-responsibility principle we outlined earlier.

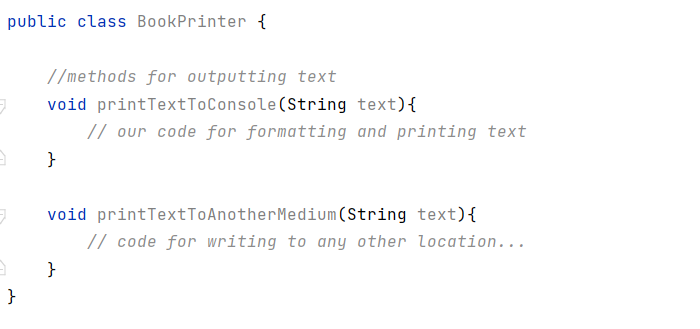

To fix this class in accordance with the single-responsibility principle, we should create a separate class that deals only with printing information about the book.

This example illustrates that whether it’s logging, validating, emailing, or anything else, we should have separate classes dedicated to a single concern. Don’t worry about having more classes; this approach makes it easier to read, refactor, and maintain. Trust me; you wouldn’t want to work with classes with thousands of lines.

Open-closed Principle

The Open-Closed Principle (OCP) states that objects or entities should be open for extension but closed for modification.

The code should be written so that, in the case of system development and the emergence of new business requirements, there is no need to change the existing code. If a single change causes many dependent modules to change, then this is a design that is difficult to modify. The OCP principle says that the program should be written so that introduced changes do not cause further changes. When this principle is respected, we add new code but do not change the existing one.

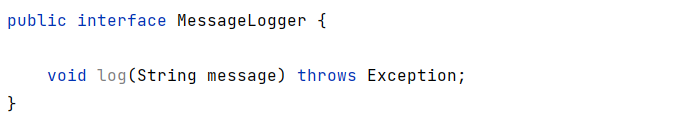

For the OCP principle, the Strategy and Template method patterns can be used. These are the most popular patterns in the OCP principle. OCP rule example:

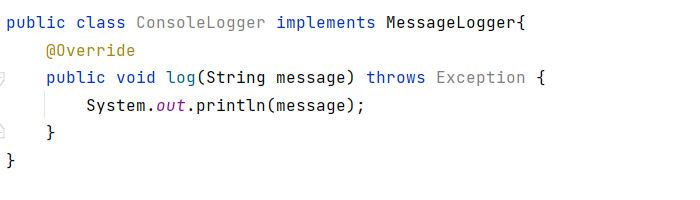

We will create separate classes for every different way of logging. The first class will be the Console Logger class, which will log messages to the console.

The second class, FileLogger, will log data to a file.

Liskov Substitution Principle

Robert C. Martin summarizes it: Subtypes must be substitutable for their base types.

Barbara Liskov, defining it in 1988, provided a more mathematical definition: If for each object o1 of type S there is an object o2 of type T such that for all programs P defined in terms of T, the behavior of P is unchanged when o1 is substituted for o2 then S is a subtype of T.

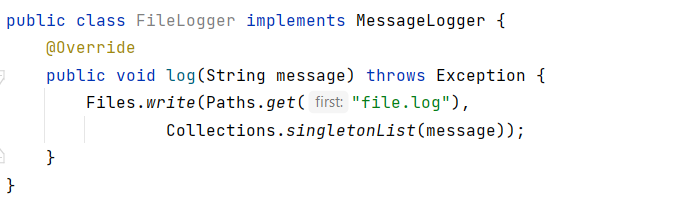

Let’s look at a bad example.

The hawk can fly because it is a bird, but what about this:

Ostrich is a bird, but it can’t fly. Ostrich class is a subtype of class Bird, but it shouldn’t be able to use the fly method, which means we are breaking the LSP principle.

Now let’s look at a good example.

Interface segregation principle

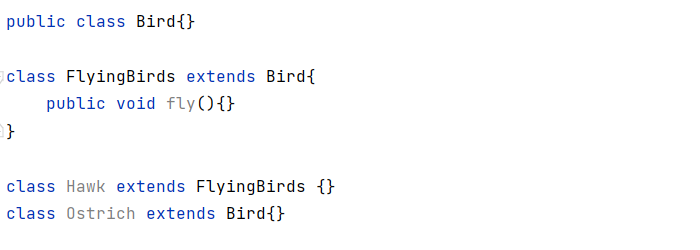

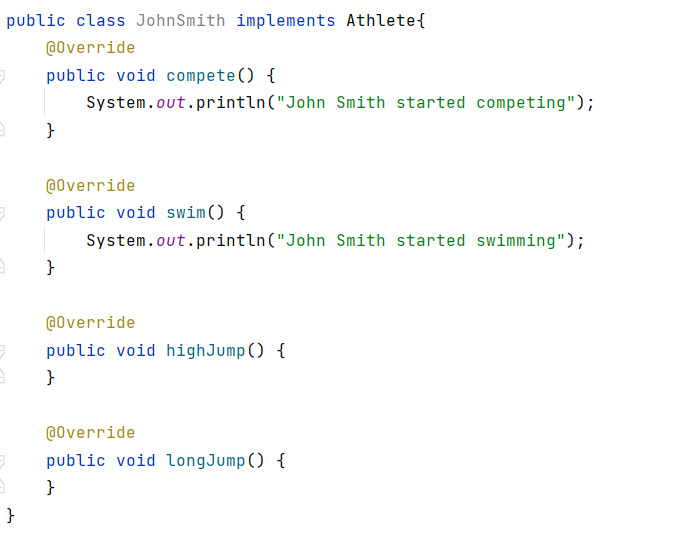

The next principle is interface segregation. The Interface Segregation Principle (ISP) states that no client should be forced to depend on methods it does not use. Imagine an interface with many methods in our codebase and that many of our classes implement this interface, although only some of its methods are implemented. In our case, the Athlete interface is an interface with some actions of an athlete:

e have added methods compete, highJump, longJump, and swim. Suppose that John Smith is a professional swimmer. By implementing the Athlete interface, we have to implement methods that John will never use, like high or long jump.

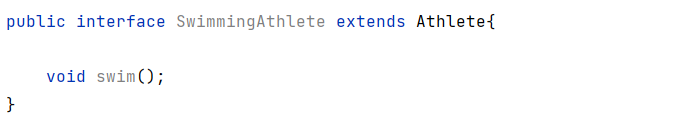

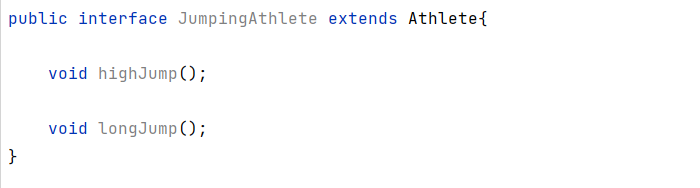

We will follow the interface segregation principle and refactor the original interface:

Then we will create two other interfaces — one for Jumping athletes and one for Swimming athletes.

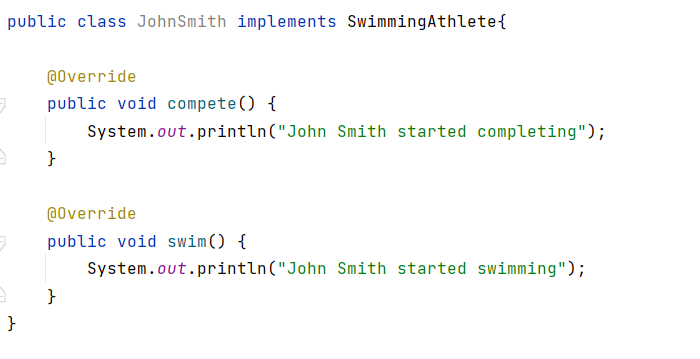

And therefore, John Smith will not have to implement actions that he is not capable of performing:

Dependency Inversion Principle

Suppose that John Smith is a swimming athlete. By implementing the Athlete interface, we have to implement methods like highJump and longJump, which John Smith will never use.

To understand the motivation behind the DIP, let’s start with its formal definition, given by Robert C. Martin in his book, Agile Software Development: Principles, Patterns, and Practices:

- High-level modules should not depend on low-level modules. Both should depend on abstractions.

- Abstractions should not depend on details. Details should depend on abstractions.

So, it’s clear that at the core, the DIP is about inverting the classic dependency between high-level and low-level components by abstracting away the interaction between them. In traditional software development, high-level components depend on low-level ones. Thus, it’s hard to reuse the high-level components. Based on other SOLID principles, if you consistently apply the Open/Closed Principle and the Liskov Substitution Principle to your code, it will also follow the Dependency Inversion Principle.

Let’s look at an example (bad example):

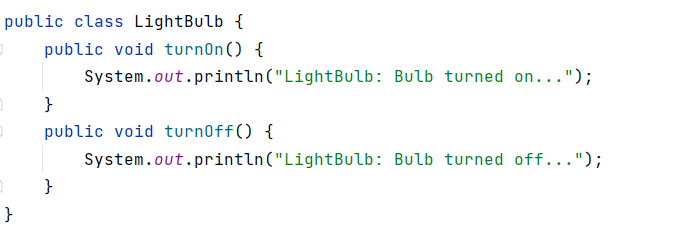

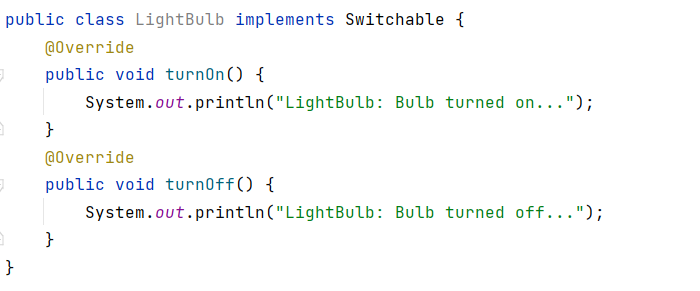

Consider the example of an electric switch that turns a light bulb on or off. We can create two classes to make it work. First, the LightBulb class.

In the class above, we wrote two methods, turnOn() and turnOff().

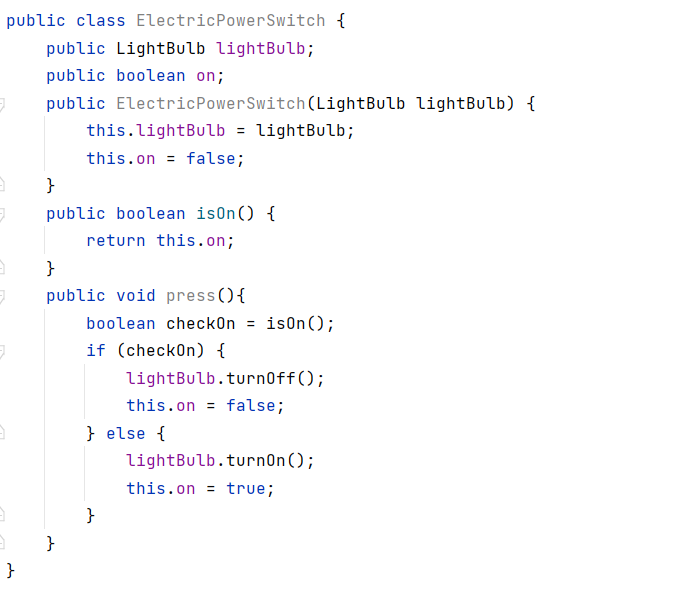

The second class is ElectricPowerSwitch.

Our switch is now ready to use, to turn the light bulb on and off. But the mistake we made is apparent. Our high-level ElectricPowerSwitch class is directly dependent on the low-level LightBulb class. The LightBulb class is hardcoded in ElectricPowerSwitch. However, a switch should not be tied to a bulb. It should be able to turn on and off other devices too, such as a fan, an AC, or the entire lighting in our backyard.

Now let’s change it to conform to the DIP principle. To do that, we need an abstraction that both the ElectricPowerSwitch and LightBulb classes will depend on.

First, create an interface for switches.

We wrote an interface for switches with the isOn() and press() methods. This interface will give us the flexibility to plug in other types of switches, say a remote control switch later on, if required.

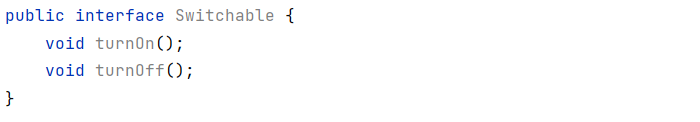

Next, we will write the abstraction in the form of an interface called Switchable with the turnOn() and turnOff() methods.

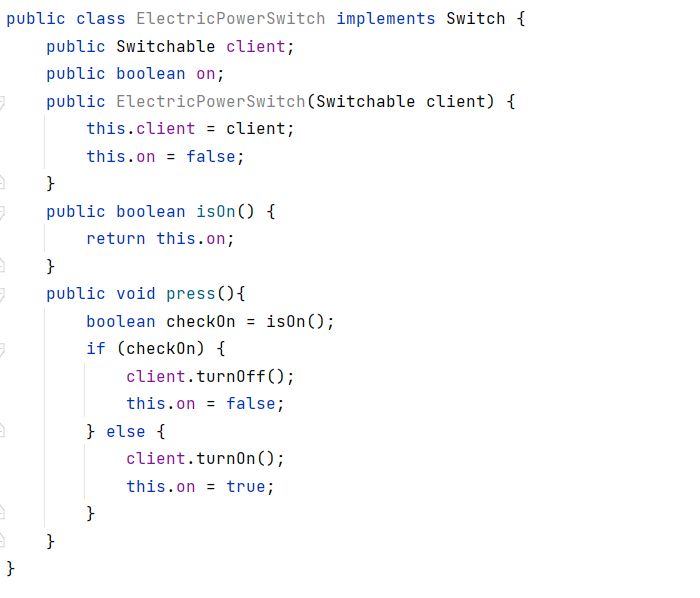

That interface allows any switchable devices in the application to implement it and provide their own functionality. Our ElectricPowerSwitch class will also depend on this interface, as shown below:

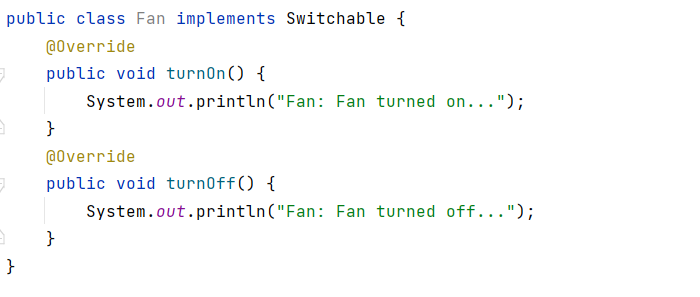

n the ElectricPowerSwitch class, we implemented the Switch interface and referred to the Switchable interface instead of any specific class in the field. We then called the interface’s turnOn() and turnOff() methods, which will be called at runtime on the object passed to the constructor. Now we can add low-level switchable classes without having to worry about modifying the ElectricPowerSwitch class (Remember the Open-Closed Principle). Let’s add two such classes.

Now our code is flexible for changes, and high-level classes don’t depend on low-level classes.

Comments