CAP Theorem

What is CAP theorem?

That statement is quite old, as it was formally introduced in 2000 by Eric Brewer, on conference named ‘Principles of Distributed Computing’ and that presentation was named ‘Towards robust distributed systems’. That’s why it’s alternative name is a Brewer theorem. The presentation can be found here.

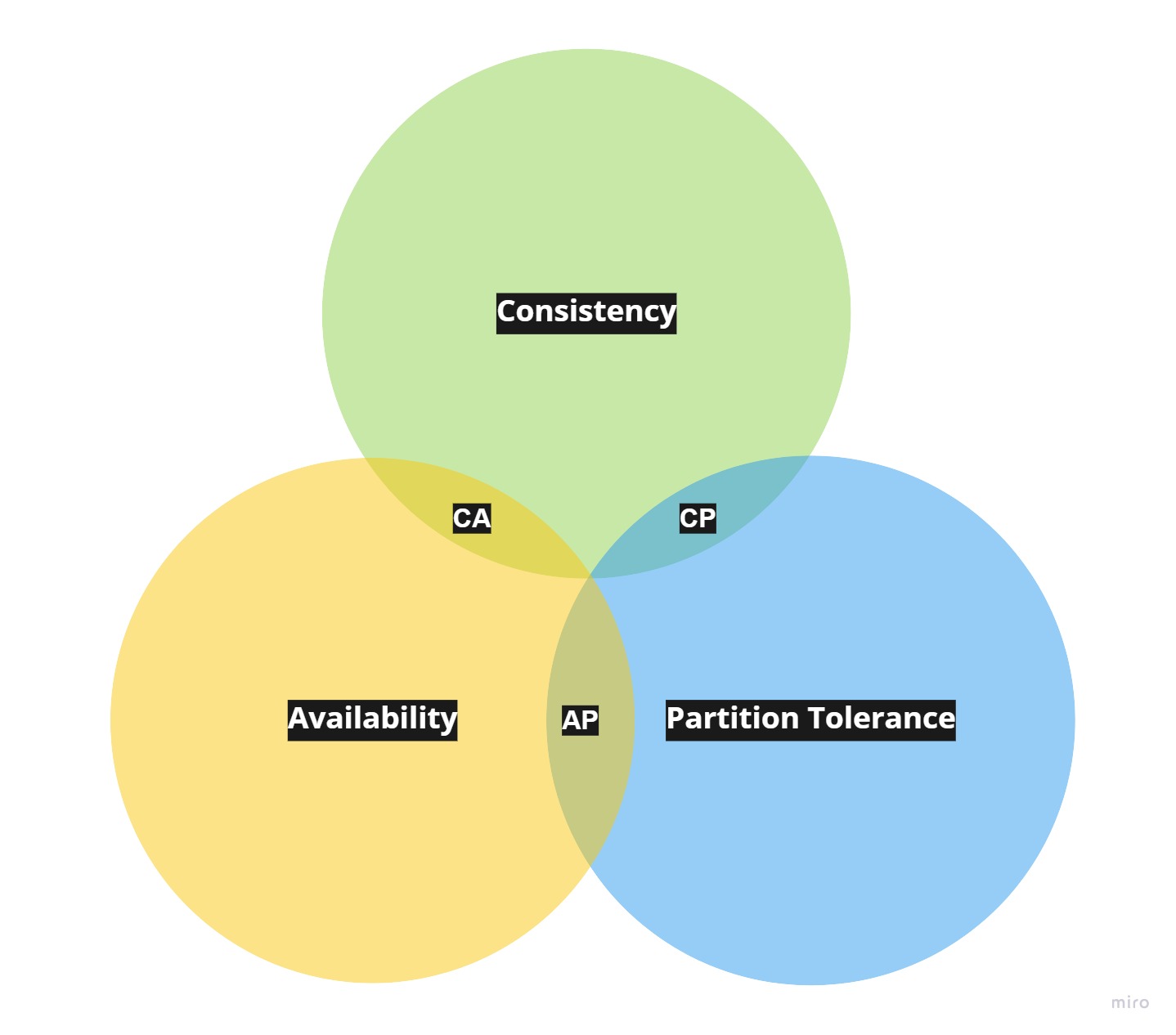

Generally, its statement sounds rather simple, namely every distributed system can guarantee two out of the following three characteristics. This is often misunderstood by people. So let’s dive a bit deeper into each of them.

Consistency

In a system is not a binary concept; it’s not simply a matter of a system being consistent or inconsistent. Instead, consistency exists along a spectrum ranging from more relaxed to stricter levels. The position of a system on this spectrum influences whether anomalies related to read and write operations may occur.

Thus, it’s not just about strong and eventual consistency, as there are variations in between these two extremes.

In the context of the CAP theorem, the highest or strongest level of consistency is typically considered, which provides linearizability. This means that if operation B starts after operation A has ended, then operation B should perceive the system in a state that reflects the changes made by operation A or a newer state.

In simpler terms, a distributed system achieves linearizability when it behaves, from the end user’s perspective, as if it were running on a single instance. This means there is no network involvement and the complexities arising from network communication between different services are eliminated. When a system behaves in this manner, it is said to exhibit linearizability.

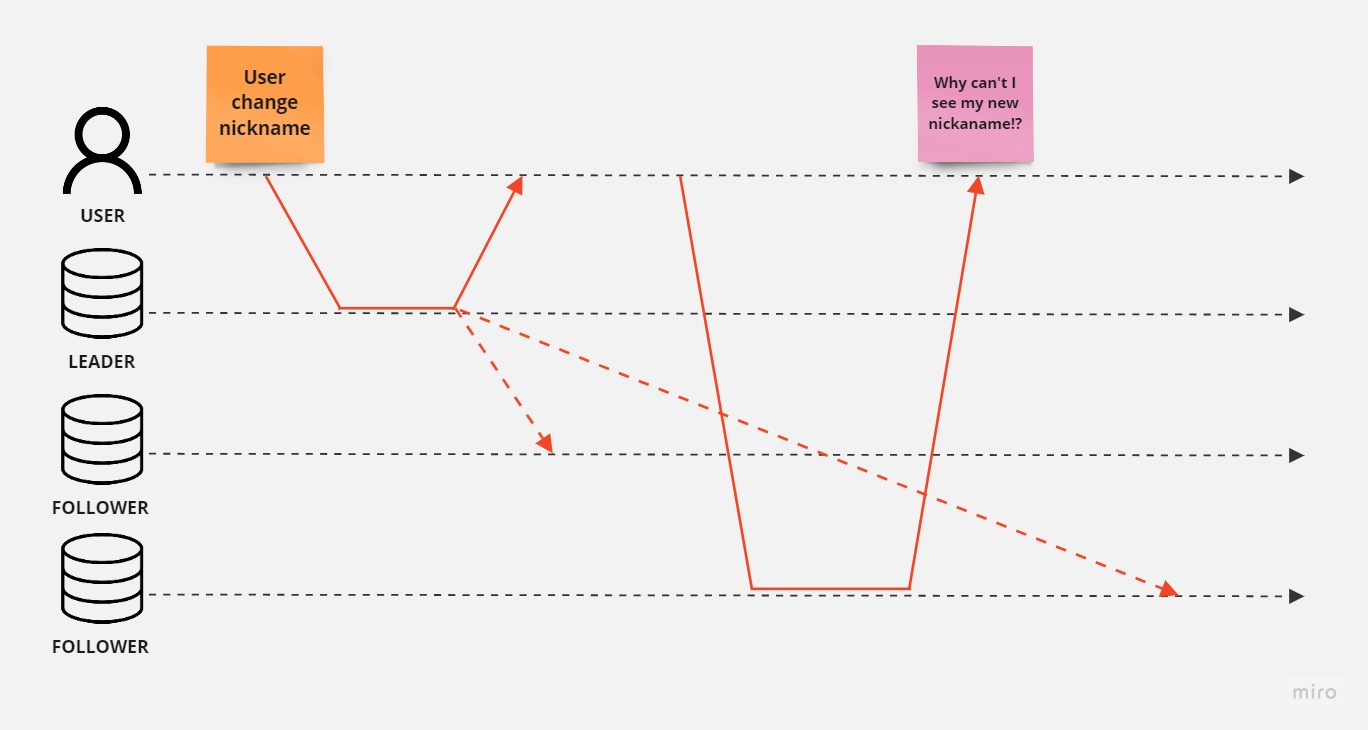

An example may be replicated database, with the master slave/leader follower topology.

Basically it works in the following way, we may read data from each replica but we can make writes just to the leader, and then based on the approach, leader in synchronized way waits until leaders update their state and i.e. return ACK, and then response to the client.

The second approach is that we write to the leader that response us immedieatly and leaders are updated in the ‘background’ in async way, fire-forget we may say. Usually it would be updated in a moment, but as some obstacles may occur related to the network, user may see the stale data, in other words outdated.

similarly it may happen that different users would see different state of the system.

Keep in mind that not every system has to have linearizability/ the strongest level consistency, as it’s quite expensive and entails certain sacrifices, and in reality most of the systems don’t need that level of consistency.

Availability

In the context of a system, signifies that every functioning node reliably provides non-error responses. This ensures that the system consistently delivers valid responses from working nodes, even when some nodes are down. In the CAP theorem, a system that meets this criterion is considered available.

Partition tolerance

Is the capability of a distributed system to continue functioning despite communication breakdowns, lost connections between nodes, or even data loss. Essentially, it ensures that the system remains operational when facing network partitions, disruptions between nodes, or data loss events.

CP (Consistency and Partition tolerance)

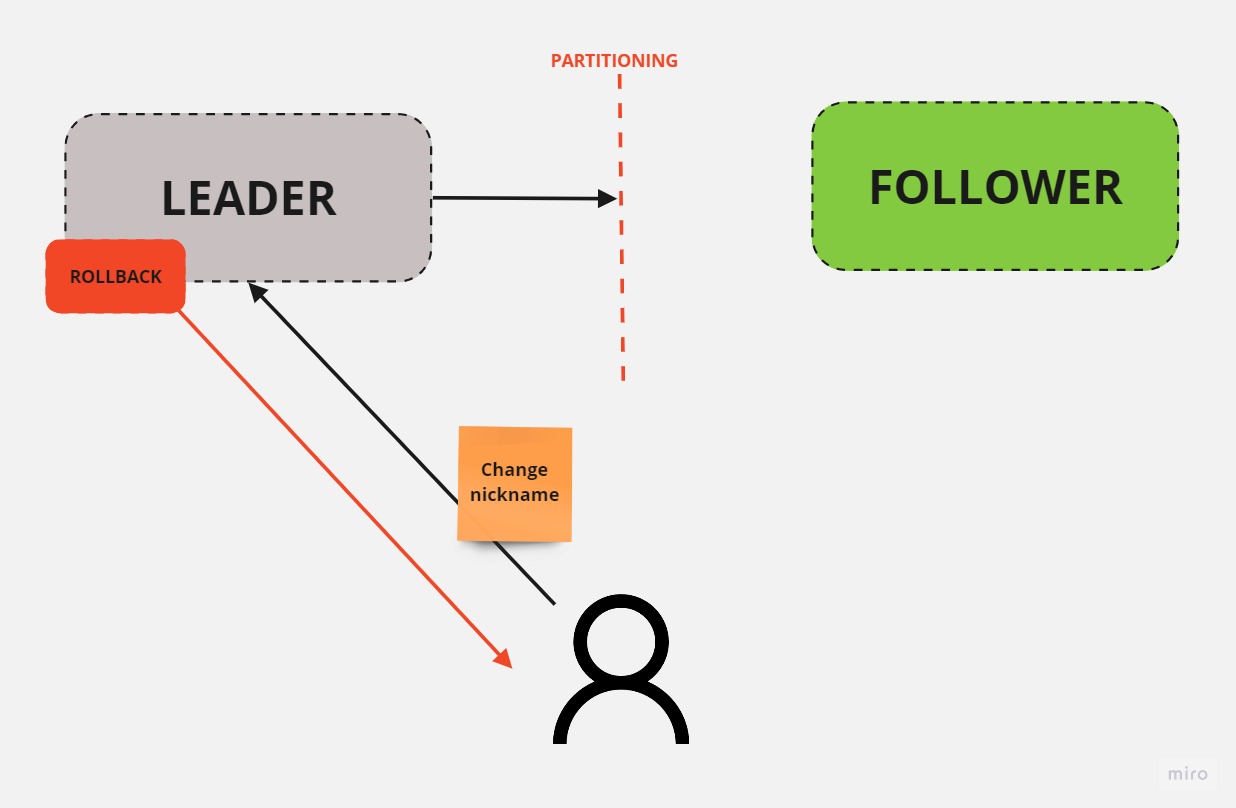

In the scenario where a request is sent to change a nickname in a system with synchronized replication, the leader node receives the request and updates its state. It then sends a synchronized request to the follower nodes to update their data. The follower nodes return an acknowledgment (ACK) to the leader node, and once the transaction is committed, the user receives a response indicating that the transaction was successful.

Regardless of which node receives the request, the returned data will be consistent due to the synchronized replication.

If partitioning occurs between the leader and follower nodes in this model, the follower will not receive the request sent by the leader to update its data. As a result, the leader node will not receive the acknowledgment from the follower, which is a part of the replication process. The leader node will eventually rollback the transaction and return a response indicating that the operation failed.

From the perspective of the CAP theorem, this model guarantees consistency, as the transaction was not committed. When requesting data from either the leader or follower nodes, the data will be consistent and have the same nickname. The model also guarantees partitioning tolerance, as the system remains operational even if the connection between the leader and follower nodes is lost. However, the model does not guarantee availability, as even though the node is operational, it returns an error. Therefore, from a CAP perspective, this model guarantees CP (consistency and partition tolerance).

AP (Availability and Partition tolerance)

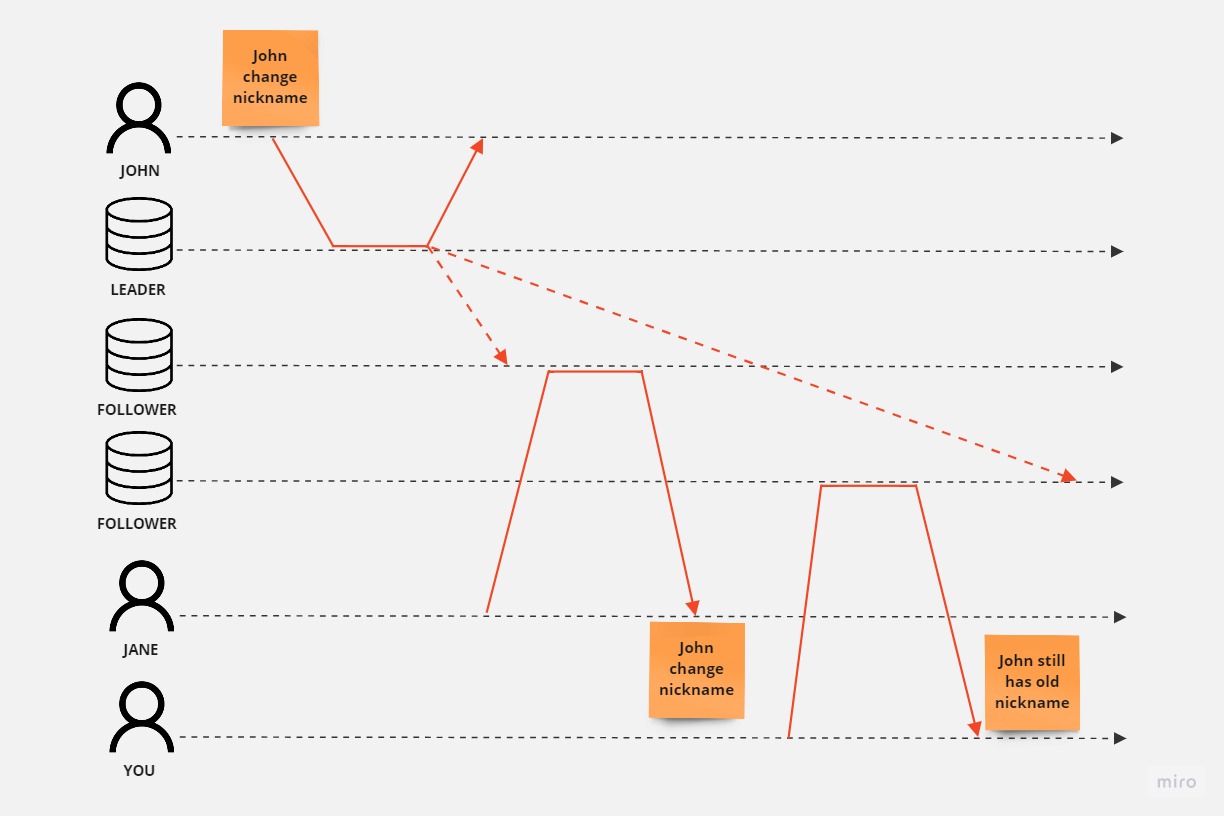

Let’s discuss the async replication approach now. Following the previous example, assume that when we send a request to the leader to change the nickname, the transaction on the leader is committed and an asynchronous request is sent to the follower (fire and forget). Meanwhile, the client receives a response with a positive result, indicating that the operation ended successfully.

What happens when a partition occurs between the leader and the follower? As the leader is sending the request to the follower in a fire-and-forget manner, it doesn’t even expect an acknowledgment from the follower and sends a positive response to the client.

In this scenario, when the customer requests data from the leader, they will receive updated data. However, if the request goes to the follower, it will return stale data. In our example, this would be the previous nickname, as the follower never received the information to update the data.

In this model, we guarantee Availability and Partition Tolerance, as even though partitioning occurs, the system still remains operational. However, we sacrifice Consistency to achieve availability, as every node will respond to requests without error, so the client may have no idea that something went wrong. The cost, as mentioned, is consistency, as different nodes may return different data.

CA (Consistency and Availability)

Imagine that our system operates using synchronized replication, and we assume that everything runs perfectly with no partitioning occurring. As a general rule, we should always receive consistent data, and the system should be available. However, the trade-off lies in the lack of Partition Tolerance (the letter P). In the CA model, when a partition does occur, the system’s reliability may be compromised.

In the CA model, the focus is on maintaining both data consistency and system availability, assuming that network partitions are rare or non-existent. The system ensures that all nodes have the same, consistent data and remain accessible to clients. However, this model is not well-suited for handling partitioning events. If a network partition does occur, the system might become partially or fully unavailable, as it is not designed to handle such situations effectively.

It is important to note that in distributed systems. The CA model prioritizes Consistency and Availability, sacrificing Partition Tolerance in the process.

Choose two out of three, right?

I guess that most people would choose the CA (Consistency and Availability) model, assuming that partitioning events are rare. However, partitioning can and will likely happen eventually, and the chances of it occurring increase over time and with nodes number. In such cases, we might not know how to handle it effectively.

The proper way to understand and think about the CAP theorem is by considering what we want to prioritize when a partition event has already occurred. We need to decide whether to sacrifice consistency to keep the system available or make the system unavailable to preserve consistency. In the end, we would always have a system that is either CP or AP. Of course, CA might still be fulfilled if we don’t have network issues, and if there’s only a 5% chance of failure and partitioning, then we still have a 95% chance that the system may be CA. However, it’s not the same as simply choosing two out of three and forgetting about the third one, the network issues, as that would be a wrong assumption, which also results from Fallacies of distributed computing.

The choice depends on our specific use case and the type of system we’re building. Does it always require consistent data? For example, consider likes on YouTube. It may happen that when we refresh the site, we see a different number of likes each time, not necessarily increasing. This could occur due to async replication and getting data from different nodes that may not have the updated data yet. In this case, the system is eventually consistent and does not have linearizability, but it’s available as each request will get a response. For such a scenario, is it a significant issue that the likes counter may differ at some point but will eventually be consistent? Probably not.

On the other hand, think about a software system that may have an impact on human lives, such as a medical application that schedules drug administration, injections, and so forth. Imagine a situation where a patient in a coma receives more doses of a drug than they should, or a dose that might be lethal. In this case, eventual consistency is not an option; it would be better to make the system unavailable and restart it rather than making decisions based on stale data.

In summary, understanding the CAP theorem involves evaluating the trade-offs between consistency, availability, and partition tolerance based on the specific requirements and goals of the system. The choice will depend on the nature of the application and its tolerance for data inconsistency or unavailability during partition events.

Comments